ESA’s Planck mission has revealed that our Galaxy contains previously undiscovered islands of cold gas and a mysterious haze of microwaves. These results give scientists new treasure to mine and take them closer to revealing the blueprint of cosmic structure.

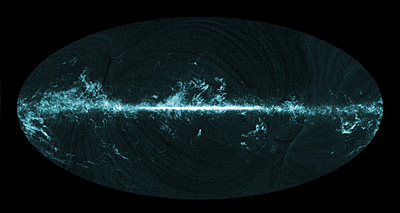

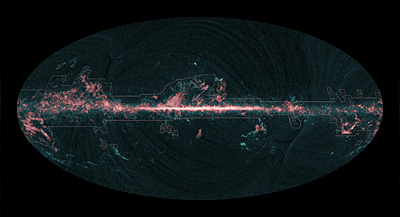

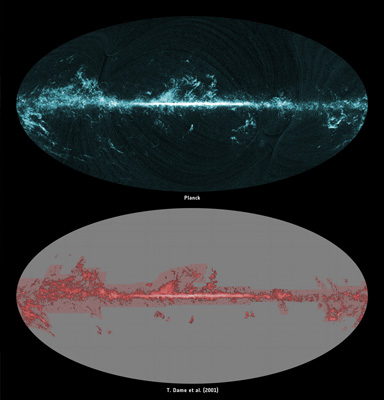

All-sky image of molecular gas seen by Planck:This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck. Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

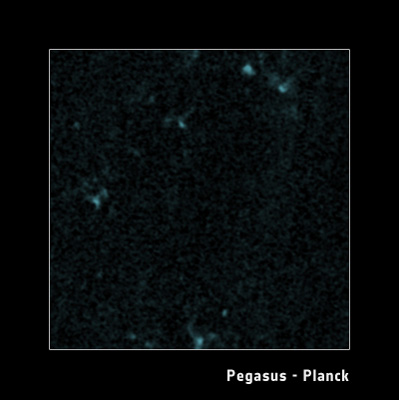

Molecular clouds in the Pegasus region: his image shows molecular clouds in the Pegasus region as seen through the glow of carbon monoxide (CO) with Planck (blue).

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

The all-sky CO map compiled with Planck data shows concentrations of molecular gas in portions of the sky that had never before been surveyed. For example, many regions at high galactic latitude, such as the Pegasus region, had not been covered by previous CO surveys. Planck's high sensitivity to CO also means that even very low-density clouds can be detected, as in the case of the Pegasus clouds.

Contacts and sources:

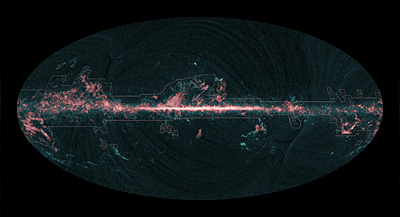

This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck (blue). A compilation of previous surveys (Dame et al. (2001)), which left large areas of the sky unobserved, has been superimposed for comparison (red). The outlines identify the portions of the sky covered by these surveys.

Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration; T. Dame et al., 2001

Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration; T. Dame et al., 2001

However, hydrogen molecules are difficult to detect because they do not readily emit radiation. Carbon monoxide forms under similar conditions and, even though it is much rarer, it emits light more readily and therefore is more easily detectable. So, astronomers use it to trace the clouds of hydrogen.

“Planck turns out to be an excellent detector of carbon monoxide across the entire sky,” says Planck collaborator Jonathan Aumont from the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Universite Paris XI, Orsay, France.

Surveys of carbon monoxide undertaken with radio telescopes on the ground are extremely time consuming, hence they are limited to portions of the sky where molecular clouds are already known or expected to exist.

All-sky image of molecular gas and three molecular cloud complexes seen by Planck: This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck. The inserts provide a zoomed-in view onto three individual regions on the sky where Planck has detected concentrations of CO: Cepheus, Taurus and Pegasus, respectively.

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

“The great advantage of Planck is that it scans the whole sky, allowing us to detect concentrations of molecular gas where we didn’t expect to find them,” says Dr Aumont.

Planck has also detected a mysterious haze of microwaves that presently defies explanation.

It comes from the region surrounding the galactic centre and looks like a form of energy called synchrotron emission. This is produced when electrons pass through magnetic fields after having been accelerated by supernova explosions.

The curiosity is that the synchrotron emission associated with the galactic haze exhibits different characteristics from the synchrotron emission seen elsewhere in the Milky Way.

The galactic haze shows what astronomers call a ‘harder’ spectrum: its emission does not decline as rapidly with increasing energies.

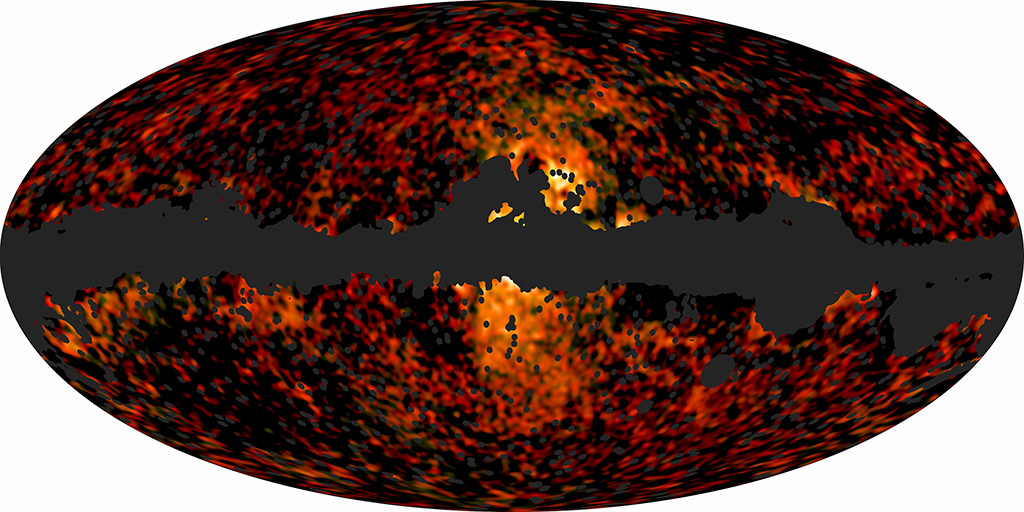

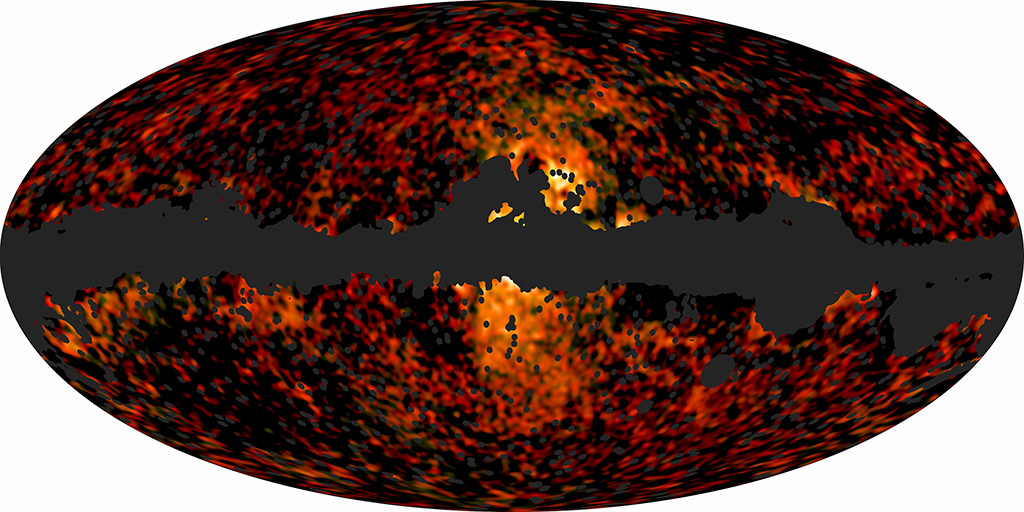

This all-sky image shows the spatial distribution over the whole sky of the Galactic Haze at 30 and 44 GHz, extracted from the Planck observations. In addition to this component, other foreground components such as synchrotron and free-free radiation, thermal dust, spinning dust, and extragalactic point sources contribute to the total emission detected by Planck at these frequencies. The prominent empty band across the plane of the Galaxy corresponds to the mask that has been used in the analysis of the data to exclude regions with strong foreground contamination due to the Galaxy's diffuse emission. The mask also includes strong point-like sources located over the whole sky.

The Galactic Haze is seen to be distributed around the Galactic Centre and its spectrum is similar to that of synchrotron emission. However, compared to the synchrotron emission seen elsewhere in the Milky Way, the Galactic Haze has a 'harder' spectrum, meaning that its emission does not decline as rapidly with increasing frequency. Diffuse synchrotron emission in the Galaxy is interpreted as radiation from highly energetic electrons that have been accelerated in shocks created by supernova explosions.

The mysterious Galactic Haze seen by Planck

The mysterious Galactic Haze seen by Planck

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

Several explanations have been proposed for the unusual shape of the Haze’s spectrum, including enhanced supernova rates, galactic winds and even annihilation of dark-matter particles. Thus far, none of them have been confirmed and the issue remains open.

So far, none of them has been confirmed and it remains puzzling.

“The results achieved thus far by Planck on the galactic haze and on the carbon monoxide distribution provide us with a fresh view on some interesting processes taking place in our Galaxy,” says Jan Tauber, ESA’s Project Scientist for Planck.

Planck’s primary goal is to observe the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the relic radiation from the Big Bang, and to measure its encoded information about the constituents of the Universe and the origin of cosmic structure.

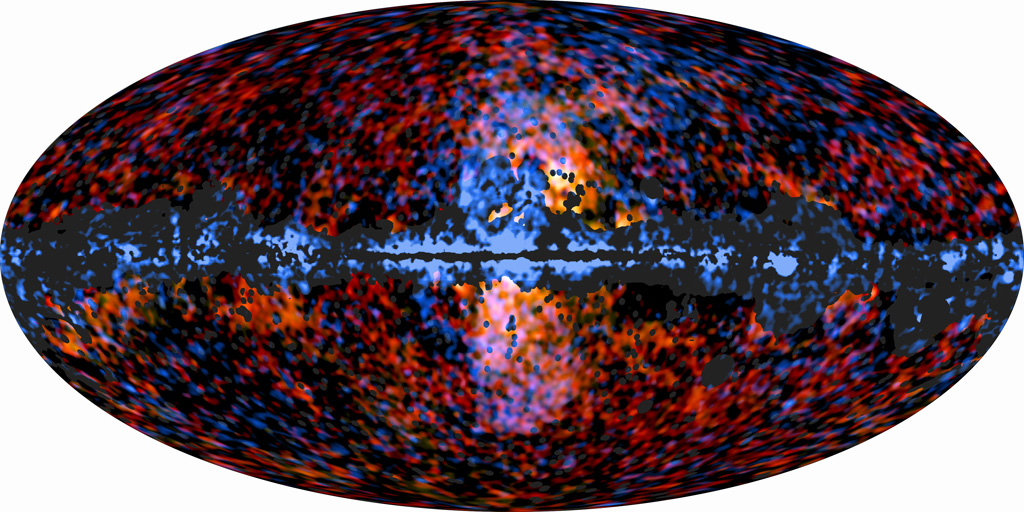

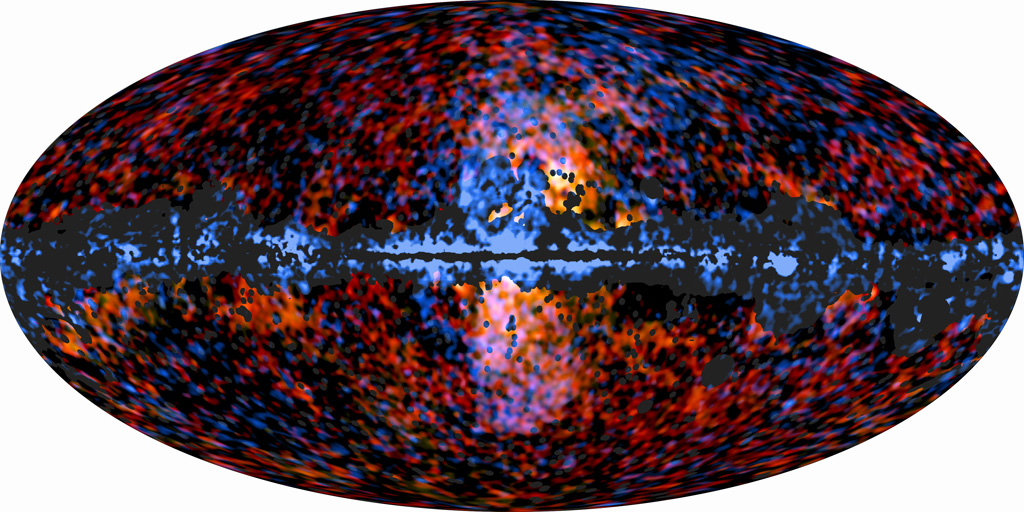

Galactic Haze seen by Planck and Galactic 'bubbles' seen by Fermi: This all-sky image shows the distribution of the Galactic Haze seen by ESA's Planck mission at microwave frequencies superimposed over the high-energy sky as seen by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The Planck data (shown here in red and yellow) correspond to the Haze emission at frequencies of 30 and 44 GHz, extending from and around the Galactic Centre.

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration (microwave); NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT/D. Finkbeiner et al. (gamma rays)

The two emission regions seen by Planck and Fermi at two opposite ends of the electromagnetic spectrum correlate spatially quite well and might indeed be a manifestation of the same population of electrons via different radiation processes.

Synchrotron emission associated with the Galactic Haze seen by Planck exhibits distinctly different characteristics from the synchrotron emission seen elsewhere in the Milky Way. Diffuse synchrotron emission in the Galaxy is interpreted as radiation from highly energetic electrons that have been accelerated in shocks created by supernova explosions. Compared to this well-studied emission, the Galactic Haze has a 'harder' spectrum, meaning that its emission does not decline as rapidly with increasing frequency.

Several explanations have been proposed for this unusual behaviour, including enhanced supernova rates, galactic winds and even annihilation of dark-matter particles. Thus far, none of them have been confirmed and the issue remains open.

The Planck image includes the mask that has been used in the analysis of the data to exclude regions with strong foreground contamination due to the Galaxy's diffuse emission. The mask also includes strong point-like sources located over the whole sky.

Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration; T. Dame et al., 2001

Molecular clouds, dense and compact regions throughout the Milky Way where gas and dust clump together, represent one of the sources of foreground emission seen by Planck. The vast majority of gas in these clouds consists of molecular hydrogen (H2), and it is in these cold regions that stars are born. Since cold H2 does not easily radiate, astronomers trace these cosmic cribs across the sky by targeting other molecules, which are present there in very low abundance but radiate quite efficiently. The most important of these tracers is CO, which emits a number of rotational emission lines in the frequency range probed by Planck's High Frequency Instrument (HFI).

The new results are being presented this week at an international conference in Bologna, Italy, where astronomers from around the world are discussing the mission’s intermediate results.

These results include the first map of carbon monoxide to cover the entire sky. Carbon monoxide is a constituent of the cold clouds that populate the Milky Way and other galaxies. Predominantly made of hydrogen molecules, these clouds provide the reservoirs from which stars are born.

Molecular clouds in the Cepheus region: This image shows the Cepheus molecular cloud complex as seen through the glow of carbon monoxide (CO) with Planck (blue). The same region is shown as imaged by previous CO surveys (Dame et al., 2001) for comparison (red).

Molecular clouds, dense and compact regions throughout the Milky Way where gas and dust clump together, represent one of the sources of foreground emission seen by Planck. The vast majority of gas in these clouds consists of molecular hydrogen (H2), and it is in these cold regions that stars are born. Since cold H2 does not easily radiate, astronomers trace these cosmic cribs across the sky by targeting other molecules, which are present there in very low abundance but radiate quite efficiently. The most important of these tracers is CO, which emits a number of rotational emission lines in the frequency range probed by Planck's High Frequency Instrument (HFI).

The new results are being presented this week at an international conference in Bologna, Italy, where astronomers from around the world are discussing the mission’s intermediate results.

These results include the first map of carbon monoxide to cover the entire sky. Carbon monoxide is a constituent of the cold clouds that populate the Milky Way and other galaxies. Predominantly made of hydrogen molecules, these clouds provide the reservoirs from which stars are born.

Molecular clouds in the Cepheus region: This image shows the Cepheus molecular cloud complex as seen through the glow of carbon monoxide (CO) with Planck (blue). The same region is shown as imaged by previous CO surveys (Dame et al., 2001) for comparison (red).

However, hydrogen molecules are difficult to detect because they do not readily emit radiation. Carbon monoxide forms under similar conditions and, even though it is much rarer, it emits light more readily and therefore is more easily detectable. So, astronomers use it to trace the clouds of hydrogen.

“Planck turns out to be an excellent detector of carbon monoxide across the entire sky,” says Planck collaborator Jonathan Aumont from the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Universite Paris XI, Orsay, France.

Surveys of carbon monoxide undertaken with radio telescopes on the ground are extremely time consuming, hence they are limited to portions of the sky where molecular clouds are already known or expected to exist.

All-sky image of molecular gas and three molecular cloud complexes seen by Planck: This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck. The inserts provide a zoomed-in view onto three individual regions on the sky where Planck has detected concentrations of CO: Cepheus, Taurus and Pegasus, respectively.

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

“The great advantage of Planck is that it scans the whole sky, allowing us to detect concentrations of molecular gas where we didn’t expect to find them,” says Dr Aumont.

Planck has also detected a mysterious haze of microwaves that presently defies explanation.

It comes from the region surrounding the galactic centre and looks like a form of energy called synchrotron emission. This is produced when electrons pass through magnetic fields after having been accelerated by supernova explosions.

The curiosity is that the synchrotron emission associated with the galactic haze exhibits different characteristics from the synchrotron emission seen elsewhere in the Milky Way.

The galactic haze shows what astronomers call a ‘harder’ spectrum: its emission does not decline as rapidly with increasing energies.

This all-sky image shows the spatial distribution over the whole sky of the Galactic Haze at 30 and 44 GHz, extracted from the Planck observations. In addition to this component, other foreground components such as synchrotron and free-free radiation, thermal dust, spinning dust, and extragalactic point sources contribute to the total emission detected by Planck at these frequencies. The prominent empty band across the plane of the Galaxy corresponds to the mask that has been used in the analysis of the data to exclude regions with strong foreground contamination due to the Galaxy's diffuse emission. The mask also includes strong point-like sources located over the whole sky.

The Galactic Haze is seen to be distributed around the Galactic Centre and its spectrum is similar to that of synchrotron emission. However, compared to the synchrotron emission seen elsewhere in the Milky Way, the Galactic Haze has a 'harder' spectrum, meaning that its emission does not decline as rapidly with increasing frequency. Diffuse synchrotron emission in the Galaxy is interpreted as radiation from highly energetic electrons that have been accelerated in shocks created by supernova explosions.

The mysterious Galactic Haze seen by Planck

The mysterious Galactic Haze seen by Planck

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

Several explanations have been proposed for the unusual shape of the Haze’s spectrum, including enhanced supernova rates, galactic winds and even annihilation of dark-matter particles. Thus far, none of them have been confirmed and the issue remains open.

So far, none of them has been confirmed and it remains puzzling.

“The results achieved thus far by Planck on the galactic haze and on the carbon monoxide distribution provide us with a fresh view on some interesting processes taking place in our Galaxy,” says Jan Tauber, ESA’s Project Scientist for Planck.

Planck’s primary goal is to observe the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the relic radiation from the Big Bang, and to measure its encoded information about the constituents of the Universe and the origin of cosmic structure.

Galactic Haze seen by Planck and Galactic 'bubbles' seen by Fermi: This all-sky image shows the distribution of the Galactic Haze seen by ESA's Planck mission at microwave frequencies superimposed over the high-energy sky as seen by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The Planck data (shown here in red and yellow) correspond to the Haze emission at frequencies of 30 and 44 GHz, extending from and around the Galactic Centre.

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration (microwave); NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT/D. Finkbeiner et al. (gamma rays)

Synchrotron emission associated with the Galactic Haze seen by Planck exhibits distinctly different characteristics from the synchrotron emission seen elsewhere in the Milky Way. Diffuse synchrotron emission in the Galaxy is interpreted as radiation from highly energetic electrons that have been accelerated in shocks created by supernova explosions. Compared to this well-studied emission, the Galactic Haze has a 'harder' spectrum, meaning that its emission does not decline as rapidly with increasing frequency.

Several explanations have been proposed for this unusual behaviour, including enhanced supernova rates, galactic winds and even annihilation of dark-matter particles. Thus far, none of them have been confirmed and the issue remains open.

The Planck image includes the mask that has been used in the analysis of the data to exclude regions with strong foreground contamination due to the Galaxy's diffuse emission. The mask also includes strong point-like sources located over the whole sky.

But it can only be reached once all sources of foreground emission, such as the galactic haze and the carbon monoxide signals, have been identified and removed.

“The lengthy and delicate task of foreground removal provides us with prime datasets that are shedding new light on hot topics in galactic and extragalactic astronomy alike,” says Dr Tauber.

“We look forward to characterising all foregrounds and then being able to reveal the CMB in unprecedented detail.”

Planck’s first cosmological dataset is expected to be released in 2013.

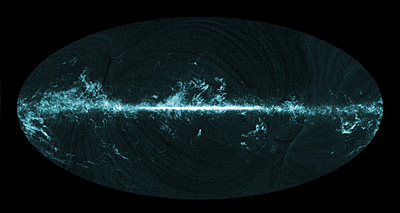

All-sky image of molecular gas seen by Planck and previous surveys: This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck (blue). A compilation of previous surveys (Dame et al. (2001)), which left large areas of the sky unobserved, is shown for comparison (red).

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration; T. Dame et al., 2001

The Planck image represents the first all-sky map of CO ever compiled. As highlighted in this image, the largest CO surveys thus far have concentrated on mapping the full extent of the Galactic Plane, where most clouds are concentrated, leaving large areas of the sky unobserved.

The CO map compiled with Planck shows concentrations of molecular gas in portions of the sky that have not been observed before, such as at high galactic latitudes, where clouds that are relatively close to the Solar System might be projected on the all-sky map. Planck's high sensitivity to CO also means that even very low-density clouds can be detected, and new details can be revealed in clouds that were already known.

“The lengthy and delicate task of foreground removal provides us with prime datasets that are shedding new light on hot topics in galactic and extragalactic astronomy alike,” says Dr Tauber.

“We look forward to characterising all foregrounds and then being able to reveal the CMB in unprecedented detail.”

Planck’s first cosmological dataset is expected to be released in 2013.

All-sky image of molecular gas seen by Planck and previous surveys: This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck (blue). A compilation of previous surveys (Dame et al. (2001)), which left large areas of the sky unobserved, is shown for comparison (red).

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration; T. Dame et al., 2001

The CO map compiled with Planck shows concentrations of molecular gas in portions of the sky that have not been observed before, such as at high galactic latitudes, where clouds that are relatively close to the Solar System might be projected on the all-sky map. Planck's high sensitivity to CO also means that even very low-density clouds can be detected, and new details can be revealed in clouds that were already known.

All-sky image of molecular gas seen by Planck:This all-sky image shows the distribution of carbon monoxide (CO), a molecule used by astronomers to trace molecular clouds across the sky, as seen by Planck.

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration This is the first all-sky map of CO ever compiled. The largest CO surveys thus far have concentrated on mapping the full extent of the Galactic Plane, where most clouds are concentrated, leaving large areas of the sky unobserved.

The CO map compiled with Planck shows concentrations of molecular gas in portions of the sky that have not been observed before, such as at high galactic latitudes, where clouds that are relatively close to the Solar System might be projected on the all-sky map. Planck's high sensitivity to CO also means that even very low-density clouds can be detected, and new details can be revealed in clouds that were already known.

The CO map compiled with Planck shows concentrations of molecular gas in portions of the sky that have not been observed before, such as at high galactic latitudes, where clouds that are relatively close to the Solar System might be projected on the all-sky map. Planck's high sensitivity to CO also means that even very low-density clouds can be detected, and new details can be revealed in clouds that were already known.

Molecular clouds in the Pegasus region: his image shows molecular clouds in the Pegasus region as seen through the glow of carbon monoxide (CO) with Planck (blue).

Credits: ESA/Planck Collaboration

The all-sky CO map compiled with Planck data shows concentrations of molecular gas in portions of the sky that had never before been surveyed. For example, many regions at high galactic latitude, such as the Pegasus region, had not been covered by previous CO surveys. Planck's high sensitivity to CO also means that even very low-density clouds can be detected, as in the case of the Pegasus clouds.

Contacts and sources:

0 comments:

Post a Comment